Presenters

- Genevieve Gellert (she/her), LCSW, Behavioral Health Consultant and LGBTQ Health Champion, Project HOME, Philadelphia, PA

- Nyasha George (she/her), MD, Primary Care Physician and LGBTQ Health Champion, Project HOME, Philadelphia, PA

Summary

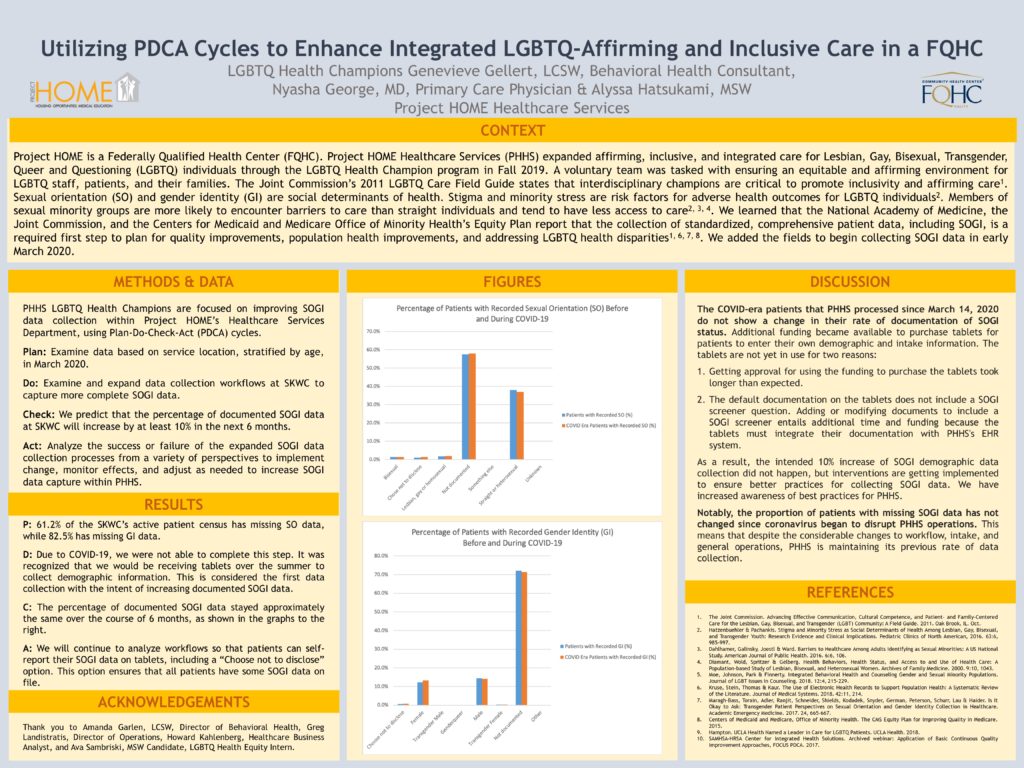

Context: Project HOME is a Federally Qualified Health Center (FQHC). Project HOME Healthcare Services (PHHS) expanded affirming, inclusive, and integrated care for Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, Transgender, Queer and Questioning (LGBTQ) individuals across all sites with the implementation of the LGBTQ Health Champion program in Fall 2019 to task a voluntary team with ensuring an equitable and affirming environment for LGBTQ staff, patients and their families. The Joint Commission’s 2011 LGBTQ Care Field Guide states that interdisciplinary champions are critical to promote inclusivity and affirming care. Sexual orientation (SO) and gender identity (GI) are social determinants of health. Stigma and minority stress are risk factors for adverse health outcomes for LGBTQ individuals (Hatzenbuehler, et al, 2016). Members of sexual minority groups are more likely to encounter barriers to care than straight individuals and tend to have less access to care (Dahlhamer, et al, 2016; Hatzenbuehler, et al, 2016; Diamant et al, 2000). LGBTQ individuals, especially LGBTQ people of color, experience chronic health issues, mental health issues, suicide, and homelessness at higher rates than heterosexual and cisgender individuals. The intersection of complex needs of people who inhabit two or more marginalized identities, such as transgender youth who are also people of color, highlights the need for integrated, affirming, and inclusive care to combat the convergence of minority stress with bio-psycho-social-spiritual issues (Moe, et al, 2018; Hatzenbuehler, et al, 2016). Motivation: PHHS LGBTQ Health Champions conducted brown-bag lunches to raise awareness across all PHHS departments about LGBTQ care needs. Through this, we learned that the National Academy of Medicine, the Joint Commission, and the Centers for Medicaid and Medicare Office of Minority Health’s Equity Plan report that the collection of standardized, comprehensive patient data, including SOGI, is a required first-step to plan for quality improvements, improve population health, and address LGBTQ health disparities (Kruse, et al, 2018; Maragh-Bass, et al, 2018; CMS, 2015). Methods and Data: PHHS LGBTQ Health Champions are focused on improving SOGI data collection at the primary and largest PHHS site, the Stephen Klein Wellness Center (SKWC), using Plan-Do-Check-Act (PDCA) cycles. P: We examined data based on service location, stratified by age, in March 2020. 61.2% of the SKWC’s active patient census has missing SO data, while 82.5% has missing GI data. D: Examine and expand data collection workflows at SKWC to capture more complete SOGI data C: We predict that the percentage of documented SOGI data at SKWC will increase by at least 10% in the next 6 months. A: Analyze the success or failure of the expanded SOGI data collection processes from a variety of perspectives to implement change, monitor effects, and adjust as needed to increase SOGI data capture within PHHS.

Objectives

- Learn the importance of SOGI data collection to improve population health over time.

- Understand how to utilize PDCA cycles to engage in improved data collection and quality improvement.

- Advocate for the implementation of LGBTQ Health Champion programs to enhance integrated LGBTQ-affirming and inclusive care.

Thinking of collecting SOGI data in an FQHC is a challenging process. I know we have struggled with it where I work – and I wish I knew what the answer was for capturing good data. Knowing who our LGBTQ+ patients are is critical as we roll out programs that are intended to address their unique healthcare needs. I could go on … Thank you for this work.